Lagunitas tea seller denied ask, gains time

In trouble with the county over decades of unpermitted building, Mr. Hoffman, 74, filed a motion in Marin Superior Court in August in defense of the continued applicability of the Marin County Architectural Commission’s 2016 designation of architectural significance for his property—a fighting argument for the preservation of his dozens of structures.

Adding urgency to his case, the county can auction off the property next year should he fail to pay outstanding taxes and penalties, which amount to over $800,000.

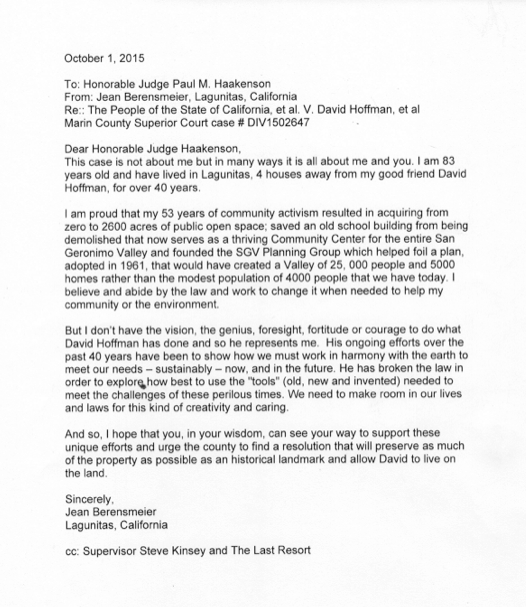

But at Friday’s hearing, Judge Paul Haakenson took guidance from county counsel Brian Case, who laid out the county’s position that the 2016 architectural significance designation was invalid. In the end, he finalized a tentative ruling that denied Mr. Hoffman’s motion, though he added some sympathetic orders.

Mr. Case explained that the architectural commission’s designation of significance was void because a court-appointed receiver who has been in control of the property since 2015 never approved it. Mr. Case provided a letter from April 2016, dated a few weeks after the commission made its determination, from the deputy director of the Building and Safety division as evidence of a timely invalidation.

Yet in a strange contradiction, Mr. Case also said the county was in favor of the receiver considering the architectural and cultural significance of Mr. Hoffman’s property, though only at his discretion and “at the appropriate time.”

For his part, the receiver, Southern California attorney Paul Beatty, deferred to the judge for direction, expressing concern about how he might both fulfill his duties and recognize the site’s architectural significance. Mr. Beatty said that in 2015 Judge Haakenson ordered him to bring the property into compliance with all state and local codes—including the state’s residential, plumbing and electrical codes—and to correct its deficiencies and violations, including by demolition.

Of particular concern to him was that unpermitted structures interfere with Alta and Cintura Creek watercourses, a violation of county code. “With respect to this much larger issue, the receiver is given to wonder: is Mr. Hoffman suggesting that the county is required to issue permits… without any restoration work being performed because a designated-architecturally-significant structure is in the way?” he wrote in a filing to the court on Sept. 28.

In his final ruling, Judge Haakenson made a few key concessions. He ordered Mr. Beatty to meet and confer with all involved parties about the possibility of reapplying to the architectural commission to consider significance on a structure-by-structure basis. Practically speaking, a designation of significance allows a structure to comply with the state’s historic building code. That code is more lenient than the building code, which has thousands of pages of prescriptive technical requirements.

Softening further, Judge Haakenson told Mr. Beatty to temporarily postpone the demolition of two structures that encroach on an adjacent public road, pending the conversation among concerned parties.

According to Judge Haakenson, this was the best he could do for Mr. Hoffman, given the county’s position. “Regardless of Marin Architectural Commission’s decision, the county seemingly is articulating that it will not approve permits, or sign off on legal compliance of any final construction, unless the structures comply with the Marin County Code, and unless the many other legal deficiencies are remedied,” he wrote in his tentative ruling. “The court is powerless to direct the county how to issue permits or approve the future construction and development. Thus, absent county agreement to ignore codes and regulations already found to exist, and apply only the Historical Building Code, it would amount to a waste of time and resources to direct the receiver to apply the Historical Building Code to guide his restoration efforts.”

This argument was perplexing to Peter Prows, Mr. Hoffman’s attorney, who not only argued that the architectural commission’s designation was never formally appealed and invalidated but also that the judge had the authority to weigh in on the matter.

“What are we doing here? We are trying to solve a problem. We have put forward a plan that was very expensive, as Your Honor can imagine, to try to make this property safe,” Mr. Prows said, referencing plans Mr. Hoffman commissioned from a San Anselmo architectural firm that delineate how the property might be brought into compliance with the historic building code.

Mr. Prows went on, “We can go down a path of finding issues that aren’t related to safety and are technical violations of this or that, and we can spend a lot of money and a lot of time and get a lot of liens on this property until Mr. Hoffman is run out of his home. Or, we can actually solve a problem—and that’s what we are trying to do.”

But Judge Haakenson was steadfast. The receiver will report back to him again in March.

After the hearing, Mr. Hoffman and his crowd of supporters convened outside the courthouse, assessing whether it had been a loss or a win. The general consensus: at least there was more time.

Mr. Hoffman, who is suffering from Lyme disease and has turned much of his attention toward his health, told the Light that he is trying to keep his stress minimal.

He continues to be supported by his community in the San Geronimo Valley and beyond. On Friday, San Francisco cinematographer A.J. Marson was documenting the most recent chapter of Mr. Hoffman’s story, and a neighbor recently took up the task of forming a nonprofit that may be able to better fund and take care of the property, dubbed the Last Resort.

John Torrey, a neighbor who partnered with Mr. Hoffman in 2016 to apply for the designation of architectural significance, said he thought the decisions at the county level were political in nature. He put pressure on District Four Supervisor Dennis Rodoni to weigh in.

“He would be a hero to the community if he did that,” Mr. Torrey said.